http://www.mechon-mamre.org/jewfaq/shabbat.htm

Shabbat

Level: Basic

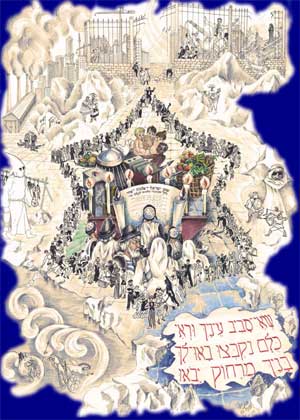

The Sabbath (or Shabbat, as it is called in Hebrew) is one of the best known and least understood of all Jewish observances. People who do not observe Shabbat think of it as a day filled with stifling restrictions, or as a day of prayer like the Christian Sunday. But to those who observe Shabbat, it is a precious gift from God, a day of great joy eagerly awaited throughout the week, a time when we can set aside all of our weekday concerns and devote ourselves to higher pursuits. In Jewish literature, poetry, and music, Shabbat is described as a bride or queen, as in the popular Shabbat hymn Lecha Dodi Likrat Kallah (come, my beloved, to meet the [Sabbath] bride). It is said "more than Israel has kept Shabbat, Shabbat has kept Israel".

Shabbat is the most important ritual observance in Judaism. It is the only ritual observance instituted in the Ten Commandments. It is also the most important special day, even more important than

Yom Kippur. This is suggested by the fact that more

aliyoth (opportunities for congregants to be called up to the Torah) are given on Shabbat than on any other day.

Shabbat is primarily a day of rest and spiritual enrichment. The word "Shabbat" comes from the

root Shin-Bet-Tav, meaning to cease, to end, or to rest.

Shabbat is not specifically a day of

prayer. Although we do pray on Shabbat, and spend a substantial amount of time in synagogue praying, prayer is not what distinguishes Shabbat from the rest of the week. Observant Jews pray every day, three times a day. See

Jewish Liturgy. To say that Shabbat is a day of prayer is no more accurate than to say that Shabbat is a day of feasting: we eat every day, but on Shabbat, we eat more elaborately and in a more leisurely fashion. The same can be said of prayer on Shabbat.

In the modern West, the five-day work-week is so common that it is forgotten what a radical concept a day of rest was in ancient times. The weekly day of rest has no parallel in any other ancient civilization. In ancient times, leisure was for the wealthy and the ruling classes only, never for the serving or laboring classes. In addition, the very idea of rest each week was unimaginable. The Greeks thought Jews were lazy because they insisted on having a "holiday" every seventh day.

Shabbat involves two interrelated commandments: to remember (zachor) the Sabbath, and to observe (shamor) the Sabbath.

We are commanded to remember Shabbat; but remembering means much more than merely not forgetting to observe Shabbat. It also means to remember the significance of Shabbat, both as a commemoration of creation and as a commemoration of our freedom from slavery in Egypt.

In

Exodus 20,10, after the Fourth Commandment is first instituted, God explains, "because for six days, the LORD made the heavens and the earth, the sea and all that is in them, and on the seventh day, he rested; therefore, the LORD blessed the Sabbath day and sanctified it". By resting on the seventh day and sanctifying it, we remember and acknowledge that God is the creator of heaven and earth and all living things. We also emulate the divine example, by refraining from work on the seventh day, as God did. If God's work can be set aside for a day of rest, how can we believe that our own work is too important to set aside temporarily?

In

Deuteronomy 5,14, when Moses reiterates the Ten Commandments, he notes the second thing that we must remember on Shabbat: "remember that you were a slave in the land of Egypt, and the LORD, your God brought you forth from there with a mighty hand and with an outstretched arm; therefore the LORD your God commanded you to observe the Sabbath day".

What does the Exodus have to do with resting on the seventh day? It is all about freedom. As said before, in ancient times, leisure was confined to certain classes; slaves did not get days off. Thus, by resting on the Sabbath, we are reminded that we are free. But in a more general sense, Shabbat frees us from our weekday concerns, from our deadlines and schedules and commitments. During the week, we are slaves to our jobs, to our creditors, to our need to provide for ourselves; on Shabbat, we are freed from these concerns, much as our ancestors were freed from slavery in Egypt.

We remember these two meanings of Shabbat when we recite kiddush (the prayer over wine sanctifying the Sabbath or a

holiday). Friday night kiddush refers to Shabbat as both zikkaron l'ma'aseh bereishit (a memorial of the work in the beginning) and zeicher litzi'at mitzrayim (a remembrance of the exodus from Egypt).

Of course, no discussion of Shabbat would be complete without a discussion of the work that is forbidden on Shabbat. This is another aspect of Shabbat that is grossly misunderstood by people who do not observe it.

Most English speakers see the word "work" and think of it in the English sense of the word: physical labor and effort, or employment. Under this definition, lighting a match would be permitted, because it does not require effort, but a waiter would not be permitted to serve food on Shabbat, because that is his employment. Jewish law prohibits the former and permits the latter. Many English speakers therefore conclude that Jewish law does not make any sense.

The problem lies not in Jewish law, but in the definition that English speakers are using. The Torah does not prohibit "work" in the 20th century English sense of the word. The Torah prohibits "melachah" (

Mem-Lamed-Alef-Kaf-Heh), which is usually translated as "work", but does not mean precisely the same thing as the English word. Before you can begin to understand the Shabbat restrictions, you must understand the word "melachah".

Melachah generally refers to the kind of work that is creative, or that exercises control or dominion over your environment. The quintessential example of melachah is the work of creating the universe, which God ceased from doing on the seventh day. Note that God's work did not require a great physical effort: he spoke, and it was done.

The word melachah is rarely used in scripture outside of the context of Shabbat and holiday restrictions. The only other repeated use of the word is in the discussion of the building of the sanctuary and its vessels in the wilderness (Exodus Chapters

31 and

35-38). Notably, the Shabbat restrictions are reiterated during this discussion (

Exodus 31,14-15 and

35,2), thus we can infer that the work of creating the sanctuary had to be stopped for Shabbat. From this, the

rabbis concluded that the work prohibited on the Sabbath is the same as the work of making the sanctuary. They found 39 categories of forbidden acts, all of which are types of work that were needed to build the sanctuary:

- Plowing

- Sowing

- Reaping

- Binding sheaves

- Threshing

- Winnowing

- Selecting

- Grinding

- Sifting

- Kneading

- Baking

- Shearing (of wool)

- Washing (of wool)

- Separating fibers (of wool)

- Dyeing

- Spinning

- Making loops

- Setting up a loom

- Weaving threads

- Separating threads

- Tying

- Untying

- Sewing

- Tearing

- Building

- Tearing down a building

- Hitting with a hammer

- Trapping

- Slaughtering

- Skinning

- Tanning a hide

- Scraping a hide

- Cutting up a hide

- Writing

- Erasing

- Drawing lines

- Kindling a fire

- Extinguishing a fire

- Taking an object from the private domain to the public domain, taking an object from the public domain to the private domain, or transporting an object in the public domain.

All of these tasks are prohibited, as well as any task that operates by the same principle or has the same purpose. In addition, the rabbis have prohibited moving any implement that is mainly used for one of the above purposes (for example, you may not move a hammer or a pencil aside from exceptional circumstances), buying and selling, and other weekday tasks that would interfere with the spirit of Shabbat.

The issue of the use of an automobile on Shabbat, so often argued by non-observant Jews, is not really an issue at all for observant Jews. The automobile is powered by an internal combustion engine, which operates by burning gasoline and oil, a clear violation of the

Torah prohibition against kindling a fire. In addition, the movement of the car would constitute transporting an object in the public domain, another violation of a Torah prohibition, and in all likelihood the car would be used to travel a distance greater than that permitted by rabbinical prohibitions. For all these reasons, and many more, the use of an automobile on Shabbat is clearly not permitted.

As with almost all of the commandments, all of these Shabbat restrictions can be violated if necessary to save a life.

At about 2PM or 3PM on Friday afternoon, observant Jews leave the office to begin Shabbat preparations. The mood is much like preparing for the arrival of a special, beloved guest: the house is cleaned, the family bathes and dresses up, the best dishes and tableware are set, a festive meal is prepared. In addition, everything that is not done during Shabbat is set up in advance: lights and appliances are set (or timers placed on them), the light bulb in refrigerator is removed, so it will not turn on when one opens it, and preparations for all the remaining Shabbat meals are made.

The Sabbath, like all Jewish days, begins at sunset, because in the story of creation in

Genesis Chapter 1, you will notice that it says at the end of the first paragraph, "And there was evening, and there was morning, one day". From this, we infer that a day begins with evening, that is, sunset. Shabbat candles are lit after a blessing is recited several minutes before sunset. Two candles are generally lit, representing the two commandments

zachor and

shamor; but one is enough, and some light seven or more.

The family then attends a brief evening service (45 minutes - that is brief by Jewish standards - see

Jewish Liturgy).

After that service, the family comes home for a leisurely, festive dinner. Before dinner, the man of the house recites Kiddush, a prayer over wine sanctifying the Sabbath. The usual prayer for eating bread is recited over two loaves of challah, a sweet, eggy bread shaped in a braid. The family then eats dinner. Although there are no specific requirements or customs regarding what to eat, meals are generally stewed or slow cooked items, because of the prohibition against cooking during the Sabbath. (Things that are mostly cooked before Shabbat and then reheated or kept warm are OK).

After dinner, the birkat ha-mazon (grace after meals) is recited. Although this is done every day, on the Sabbath, it is done in a leisurely manner with many upbeat tunes.

By the time all of this is completed, it may be 9PM or later. The family has an hour or two to talk or study Torah, and then go to sleep.

The next morning Shabbat services begin around 9AM and continue until about noon. After services, the family says kiddush again and has another leisurely, festive meal. A typical afternoon meal is cholent, a very slowly cooked stew. A

recipe is below. By the time birkat ha-mazon is done, it is about 2PM. The family studies Torah for a while, talks, takes an afternoon walk, plays some checkers, or engages in other leisure activities. A short afternoon nap is not uncommon. It is required to have a third meal before the Sabbath is over. This is usually a light meal in the late afternoon.

Shabbat ends at nightfall, when three stars are visible, approximately 40 minutes after sunset. At the conclusion of Shabbat, the family performs a concluding ritual called Havdalah (separation, division). Blessings are recited over wine, spices, and candles. Then a blessing is recited regarding the division between the sacred and the secular, between the Sabbath and the working days, etc.

As you can see, Shabbat is a very full day when it is properly observed, and very relaxing. You really do not miss being unable to turn on the TV, drive a car, or go shopping.

Cholent is a traditional Shabbat dish, because it is designed to be cooked very slowly. It can be started before the Sabbath and is ready to eat for lunch the next day. The name "cholent" supposedly comes from the French words "chaud lent" meaning hot slow. If French seems like a strange source for the name of a traditional Jewish dish, keep in mind that the ancestors of the

Ashkenazic Jews traveled from Israel to Germany and Russia by way of France.

- 2 pounds fatty meat (you can use stewing beef, but brisket is more common)

- 2 cups dry beans (navy beans, great northern beans, pintos, limas are typical choices).

- 1 cup barley

- 6 medium potatoes

- 2 medium onions

- 2 tablespoons flour

- 3 tablespoons oil

- garlic, pepper, and paprika to taste

- water to cover

Soak the beans and barley until they are thoroughly softened. Sprinkle the flour and spices on the meat and brown it lightly in the oil. Cut up the potatoes into large chunks. Slice the onions. Put everything into a Dutch oven and cover with water. Bring to a boil on the stove top, then put in the oven at 250 degrees before Shabbat begins. Check it in the morning, to make sure there is enough water to keep it from burning but not enough to make it soggy. Other than that, leave it alone. By lunch time Shabbat afternoon, it is ready to eat.

This also works very well in a crock pot on the low setting, but be careful not to put in too much water!

The word "Torah" is a tricky one, because it can mean different things in different contexts. In its most limited sense, "Torah" refers to the Five Books of Moses: Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, and Deuteronomy. But the word "torah" can also be used to refer to the entire Hebrew Bible (the body of scripture known to non-Jews as the Old Testament and to Jews as the Tanakh or Written Torah), or in its broadest sense, to the whole body of Jewish law and teachings.

The word "Torah" is a tricky one, because it can mean different things in different contexts. In its most limited sense, "Torah" refers to the Five Books of Moses: Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, and Deuteronomy. But the word "torah" can also be used to refer to the entire Hebrew Bible (the body of scripture known to non-Jews as the Old Testament and to Jews as the Tanakh or Written Torah), or in its broadest sense, to the whole body of Jewish law and teachings. The scriptures that we use in services are to be written in scrolls on

The scriptures that we use in services are to be written in scrolls on  The scrolls are kept in a cabinet in the

The scrolls are kept in a cabinet in the